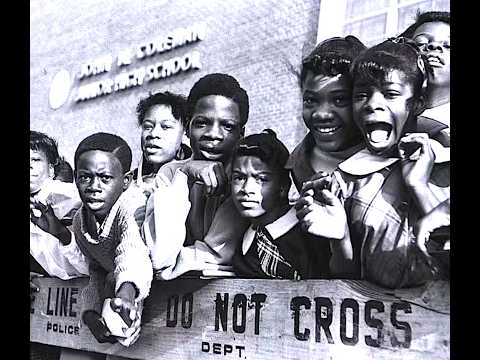

The 1968 school battle in New York City as shown in this clip, called the Ocean Hill-Brownsville conflict, was a major and highly controversial event centered on community control of schools. The dispute arose when the city, as part of an experimental decentralization program, granted a mostly Black and Puerto Rican Brooklyn community the authority to manage its local schools. The community, frustrated by years of inadequate education and underrepresentation, sought to hire teachers who understood and could relate to their students' cultural backgrounds.

The conflict escalated when the local governing board dismissed 19 mostly white teachers and administrators, citing poor performance and a need for more community-sensitive staff. This led to strong opposition from the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which argued that the teachers’ removal violated union protections and due process. Tensions quickly intensified, with allegations of racism, anti-Semitism (many of the dismissed teachers were Jewish), and accusations of union-busting. Strikes by the UFT paralyzed the city’s schools, and the conflict highlighted deep racial, social, and political divides, ultimately resulting in the city regaining control and largely ending the community-control experiment.

Comparing the school control debates then and now reveals both similarities and differences.

The central theme in both 1968 and today is who should have control—local communities or central authorities. In 1968, community members sought autonomy over their schools to tailor education to the specific needs of their neighborhoods. Today, debates still center on autonomy, with some advocating for greater local or parental control (e.g., through charter schools or homeschooling) and others pushing for standardized, centralized control to ensure uniform education quality.

Unions played a prominent role in 1968, primarily concerned with job security, collective bargaining rights, and due process. Today, teachers' unions continue to be influential, defending teachers' rights while also engaging in debates over curriculum, funding, and educational policies (e.g., opposition to charter schools, standardized testing, and merit-based pay).

The 1968 battle was explicitly racial, with Black and Puerto Rican communities demanding that schools better serve their children. Today, racial and equity issues persist but are often reframed around disparities in school funding, discipline practices, and access to quality education. Issues like curriculum content, racial representation among educators, and the presence of police in schools reflect ongoing concerns about race and equity.

While the 1968 battle was not focused on curriculum content, today’s school conflicts frequently involve ideological disputes over what students should learn. This includes debates over topics like American history, racial injustice, gender identity, and climate change. Parents, school boards, and local governments sometimes clash over what they see as politically biased or inappropriate materials.

In 1968, the battle was over public school control. Today, alternatives like charter schools and private schools have gained popularity, often creating competition with public schools and prompting debates over resource allocation and public accountability.

In both eras, the struggle for control reflects broader societal concerns—how education should serve diverse communities, what role teachers' unions should play, and how educational policies align with political, cultural, and racial values. While the actors and issues have evolved, the underlying tension over who holds the power to shape education remains strikingly similar.